| |||

|

The Emissia.Offline Letters Электронное научное издание (педагогические и психологические науки) | |||

|

Издается с 7 ноября 1995 г. Учредитель: Российский государственный педагогический университет им. А.И.Герцена, Санкт-Петербург | |||

| |||

|

---------- Кац Нора

Григорьевна

Модель дидактической подготовки преподавателя иностранного языка Аннотация Ключевые слова: преподаватель иностранного языка, дидактическая подготовка, профессионально-ориентированная подготовка, содержание профессионально-ориентированной подготовки преподавателей иностранного языка. ---------- Nora G. Kats Postgraduate research student, Al.Herzen State Pedagogical University of Russia, Saint Petersburg The model of foreign language teacher didactic training

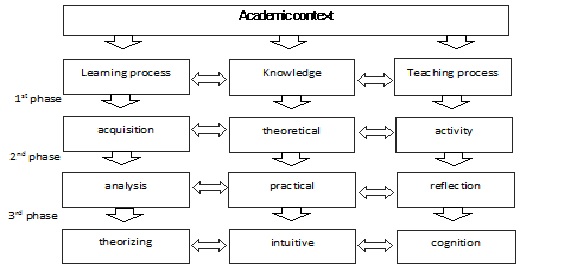

Abstract Key words: second language teacher education, second language teacher development, second language teacher training, teacher learning, foreign language teaching, second language teacher knowledge, didactic training. ---------- Language teacher education has been defined as a “bridge” that links the knowledge in the field with the practices performed in the classroom with the help of individuals who are being educated as teachers [1,2]. Although the questions on language teacher education have a “long-standing history”, receiving a lot of attention in scientific research, there is still no agreement on what constitutes the knowledge base of a second language teacher and what forms and ways should be applied to ensure its development [1], especially in the contexts of language teacher education, teacher training and teacher development. Language Teacher education, teacher training, teacher development and teacher learning. Language teacher education is most commonly regarded as an academic background and qualifications needed for a second language teacher to join the teaching profession. Language teacher education is institutionally based and delivered under specific curricula with respect to national and university education policies. Being a broad, multifaceted notion, current language teacher education is “a microcosm of teacher education” where quite a lot of trends are drawn from theory and practice in general teacher education [3] (p.34). The recent years might be viewed as a constant search for a theory of language teaching, generating a wide range of views, trends and shifts in language teacher education. The most prominent shift is referred to teachers’ perception and could be featured as a transition from passive, “readymade” knowledge consumers to “knowledge builders” and “decision-makers”, in light of the development of constructivist, sociocultural, dynamic, cognitive approaches to language teacher education. Teachers are also viewed as “reflective practitioners” as they reflect on their performance and discuss their personal insights [4]. Traditionally, language teacher education has been balancing between education, as a theoretical foundation, and training where the latter has been emphasizing the necessity of skills development, needed for teachers’ performance in the classroom [3]. The role of training is to introduce a varied number of practical solutions to common classroom problems, equip a teacher with a sufficient number of teaching techniques, demonstrate a wide range of methodological choices [5]. Teacher training is solution-oriented and quite instructional in its nature, as, most commonly, it provides the guidelines on what to do and how to behave in the classroom. In academic context of teacher education, teacher training is more likely to be referred as teaching practice or so called “field practice”, which aims at cultivating the practical knowledge of prospective (future) teachers [6]. Teacher training is widely associated with professional development of a teacher, though the distinction between these two has been extensively advocated by a number of researchers [3,5,6]. Thus, teacher development is considered to be a “life-long process of growth” which might involve collaborative or individual learning with active reflections on practices [3]. From this perspective, the development is something that can be done only by oneself on own accord, whereas training can be managed and presented by others [7]. Besides that, teacher development is thought to be tightly connected with personal and moral dimensions, as it presents an individual moral commitment [5]. Teacher education, teacher training and teacher development are interrelated concepts, when viewed as a process, are quite often addressed from the perspective of teacher learning. Teacher learning has been mostly perceived as a cognitively driven process, “theorization of practice” which results in teacher cognition[8]. It is worth mentioning that this process is considered as socially and culturally situated, context bound and dependent on personal motives and beliefs [8,9]. Teacher learning is a process of developing the appropriate knowledge in the field, though it is not viewed as “translating knowledge and theories into practice”, but as building new knowledge and theories through “participating in specific social contexts and engaging in particular types of activities and processes [10](p.6). So, what kind of knowledge should a teacher acquire and construct? How could the knowledge be developed? What is the knowledge base of a foreign language teacher? These questions of what an effective teacher needs to know and how this knowledge could be developed are still seeking their answers [11]. Thus, there is a clear demand for further investigation. Areas of teacher knowledge. Traditionally, there have been two main areas within the field of SLTE, focusing on teaching skills and pedagogic issues and on theoretical underpinnings of language knowledge and language learning. These areas of knowledge have been contrasted as knowledge about and knowledge how [10]. Knowledge about or content knowledge is delivered according to the academic curriculum of SLTE program, including, for instance, language analysis, discourse analysis, lexicology, phonology, methodology etc. Knowledge how, with its core concept of pedagogical content knowledge, is referred to practical knowledge, - the ability to transform the knowledge into learnable forms, the knowledge that can be used by teachers to manage and facilitate the learning environment in the classroom. L. Shulman identifies several areas and forms of teacher knowledge. Content knowledge, in his opinion, comprises a) subject matter content knowledge, b) pedagogical content knowledge, c) curricular knowledge. Subject matter content knowledge is viewed as knowledge of a particular subject, its theories, rules and domains and the ability to translate this subject to students in a way of interpreting, analyzing and contrasting its content. Basically, the teachers are supposed to understand not only that “something is so, but why it so” [12](p.9). Pedagogical content knowledge is characterized as knowledge needed to teach the subject matter content knowledge, namely forms of representation, examples, illustrations etc. This is the knowledge needed to form and represent the subject in a learnable manner. Curricular knowledge is about knowing the curriculum of a specific organization at a specific level and being aware of a wide range of materials and resources available for teaching the subject at varied levels and in varied educational institutions at different levels. Apart from content knowledge, L. Shulman differentiates between the forms of knowledge such as prepositional knowledge, case knowledge and strategic knowledge, meaning that the scope of knowledge that is beyond the content, pedagogy and curriculum, for instance, the knowledge of philosophy of history and education, methods of classroom organization and management, psychological aspects of learning and teaching etc., should be referred as forms of knowledge. The author argues that much of what is being taught to teachers is in the form of prepositions which are grouped as principles, maxims and norms. The principle is drawn from empirical research whereas maxims represent the essence of practice, and norms characterize the values, beliefs, ideological, philosophical and moral commitments. Strategic knowledge appears when a teacher faces the situations where no simple solution can be immediately made. It arises out of a contradiction in principles, norms, regulations and beliefs. L. Shulman states that maxims are complimented by case knowledge, which is explained as the knowledge of specific, well-documented and well-explained events. The cases might be the examples of specific situations occurred in practice, completed with particular contexts, beliefs, thoughts and feelings [12]. D.C. Berliner states that case knowledge is a part of practical knowledge of teachers, which is defined as “proximal guide for a good deal of teachers’ classroom behavior” [13] (p.20). Practical knowledge is acquired with practice as a result of encountering varied situations in different educational settings, which in their turn, form practical cases of a teacher. With the growth of expertise, the teacher is likely to operate practical cases more that theoretical underpinnings when making decisions in the classroom. D.C. Berliner identifies core features of practical knowledge. Firstly, it is action-oriented and acquired “without direct help form others” [14]( p.206). Secondly, it is always context-bound and thirdly, it is always implicit or tacit (intuitive) as in most of the cases teachers fail to “articulate their practical knowledge” [14](p.206). R. Day proposes another view on teacher knowledge base. He suggests that teacher knowledge consists of four domains, namely: a) content knowledge –knowledge of the subject matter; b) pedagogic knowledge – knowledge of common beliefs, practices and theories regardless the subject being taught c) pedagogic content knowledge – the knowledge of how to represent the content to students, awareness of students’ difficulties and difficult subject areas; d) support knowledge – the knowledge of other disciplines that support the approaches to teaching content. He considers these areas of knowledge in the “professional knowledge source continuum”, consisting of a variety of experiences and activities that result in professional knowledge about teaching. The knowledge that appears within the practice of teaching in the classroom is termed as “experiential knowledge”[15] (p.2-3). The recognition of professional knowledge source continuum is quite beneficial as it, first of all, advocates the idea of multiple sources for knowledge development, secondly, it views the knowledge development as a learning process. Later J. Richards suggests to recognize six dimension of knowledge that constitute the knowledge base of a second language teacher: (a) theories of teaching; (b) teaching skills; (c) communication skills and language proficiency; (d) subject matter knowledge; (e) pedagogical reasoning and decision making; (f) contextual knowledge. This framework accumulates the core ideas of subject matter, pedagogical knowledge, context and language proficiency, that was earlier emphasized by R. Lafayette [11]. Although this framework has been well- acknowledged and widely used in research, it does not fully address the process and activity of teaching itself. Thus, D. Freeman and K. Johnson propose the framework that focuses on the activity of teaching from sociocultural perspective. It consists of 3 dimensions: a) teacher-learner; b) social context; c) the pedagogical process, meaning that the activity of teaching occurs in different social, cultural and institutional contexts where main focus should be switched to the teacher, performing this activity and the pedagogy being used in its support. In our opinion, this idea is valuable over several reasons. First of all, we cannot disapprove the role of culture in educational process and social nature of classroom interactions as well as we do understand that teaching appears in different sociocultural contexts influenced by different levels of education. Secondly, it is quite common to debate on the necessity to keep a learner-centered approach when teaching a foreign language to students, though, surprisingly less attention being paid to the need of doing the same when teaching prospective teachers in academic settings. Current educational models used in academic contexts (“knowledge transmission”, “apprentice-expert” [15],“observe-apply”) in most of the cases fail to address the idea of personal knowledge construct (constructivist approach) and its practical appropriation in a certain social and cultural environment (sociocultural approach). Thirdly, the fact of switching the focus to teachers’ activity and considering the dichotomy of teacher being the teacher and the learner encourages the idea to view the processes of teacher learning, teacher teaching and knowledge acquisition as a didactic process, supported by a model of didactic training. Learning and teaching are interrelated processes that happen in a specific classroom. The classroom is always a specific context which can be artificially set to meet the learning needs or can be viewed as a “natural” environment. Teacher education, in a majority of cases, happen in academic settings, such as universities, colleges or educational institutions where the most common way to develop the knowledge is to introduce students to theory. Though to develop different areas of knowledge, different contexts should be set by means of varied activities aimed at introducing diverse teaching experiences. The knowledge development is not only about distinguishing the knowledge areas, but also about understanding what phases should a prospective teacher undergo to develop such knowledge. We believe that specific areas of teacher knowledge are likely to be reconsidered with the development of society, technological progress, economics etc. For instance, a couple of decades ago, there was a rare research focusing on the technological knowledge of a teacher, though nowadays, the area of technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPCK) is being widely investigated due to the rapid development of technology [16]. We do not state that there is no need to research the knowledge base of a foreign language teacher with regard to its core disciplines and skills to be developed, there definitely is, though we do claim that it is equally important to understand the nature of second language teachers’ learning and teaching, bound to the academic context. Thus, we argue the necessity to develop a model of didactic teacher training that would explain the interrelation of learning and teaching processes in an academic context. The model of foreign language teacher didactic training. Research on didactics in its broad definition refers to all kinds of “teaching-studying-learning process”[17]. It is always connected to the context of society and institution [17]. Didactics focuses on the forms, methods and materials used for teaching and learning, their interrelations and principles. Didactic knowledge, as one of the outcomes of prospective teachers’ academic education is shaped in line with relevant phases of teaching and learning processes. We differentiate between three knowledge dimensions, being theoretical (pedagogical content, subject content, curricular knowledge), practical (case knowledge and professional behaviors), intuitive (fully appropriated, tacit knowledge). Based on current scientific studies review, we assume that learning is a cognitive process that shows dynamics through acquisition, analysis and theorizing phases whereas teaching is a cognitive behavioral process that changes from activity through reflection to cognition.

Pic.1. The model of foreign language teacher didactic training We suppose that considering the teacher training as a didactic process, where a teacher acts as both a learner and a teacher, might ensure effective didactic knowledge development of prospective foreign language teachers as well as equip them with appropriate techniques for constructing their own knowledge and growing professionally. Involving the prospective teachers in their personal knowledge construct by means of reflection, analysis and through their activity, will ease their professional adjustment and might decrease the risk of profession dropouts. Literature [1] Farrell T S C 2018 Second Language Teacher Education and Future Directions TESOL Encycl. English Lang. Teach. 1–7 [2] Freeman D 2002 The hidden side of the work: Teacher knowledge and learning to teach. A perspective from north American educational research on teacher education in English language teaching Lang. Teach. 35 1–13 [3] Crandall J (Jodi) 2000 Language Teacher Education Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 20 34–55 [4] Richards J C and Lockhart C 2007 Reflective Teaching in Second Language Classrooms (New York: Cambridge University Press) [5] Mann S 2005 The language teacher’s development Lang. Teach. 38 103–18 [6] Lv Y 2014 The professional development of the foreign language teachers and the professional foreign language teaching practice Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 4 1439–44 [7] Wallace M J 1991 Training foreign language teachers: A reflective approach (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) [8] Widdowson H G 2003 “Expert beyond experience”: Notes on the appropriate use of theory in practice. In. D. Newby (ed.) Mediating between Theory and Practice in the Context of Different Learning Cultures and Languages . Strasbourg/Graz: Council of Eur [9] Burns A and Richards J 2009 The Cambridge Guide to Second Language Teacher Education (New York: Cambridge University Press) [10] Richards J C 2008 Second Language Teacher Education Today The growth of SLTE RELC J. 39 158–77 [11] Faez F 2011 Developing the Knowledge Base of ESL and FSL Teachers for K-12 Programs in Canada Can. J. Appl. Linguist. 14 29–49 [12] Shulman L S 1986 Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching 15 4–14 [13] Berliner D C 2004 Expert Teachers : Their Characteristics , Development and Accomplishments la Teor. a l’aula Form. del Profr. Enseny. las ciències Soc. 13–28 [14] Berliner D C 2004 Describing the behavior and documenting the accomplishments of expert teachers Bull. Sci. Technol. Soc. 24 200–12 [15] Day R 1993 Models and the Knowledge Base of Second Language Teacher Education Work. Pap. Second Lang. Stud. 11 1–13 [16] Koehler M J and Mishra P 2005 What happens when teachers design educational technology? the development of technological pedagogical content knowledge 32 131–52 [17] Kansanen P and Meri M 1999 Didactic relation in the teaching-studying-learning process TNTEE Publ. 2 107–16

| |||

|

| |||

| Copyright (C) 2019, Письма в Эмиссия.Оффлайн (The

Emissia.Offline Letters):

электронный научный журнал ISSN 1997-8588 (online), ISSN 2412-5520 (print-smart), ISSN 2500-2244 (CD-R) Свидетельство о регистрации СМИ Эл № ФС77-33379 (000863) от 02.10.2008 от Федеральной службы по надзору в сфере связи и массовых коммуникаций При перепечатке и цитировании просим ссылаться на " Письма в Эмиссия.Оффлайн ". Эл.почта: emissia@mail.ru Internet: http://www.emissia.org/ Тел.: +7-812-9817711, +7-904-3301873 Адрес редакции: 191186, Санкт-Петербург, наб. р. Мойки, 48, РГПУ им. А.И.Герцена, корп.11, к.24а Издатель: Консультационное бюро доктора Ахаяна [ИП Ахаян А.А.], гос. рег. 306784721900012 от 07.08.2006. |